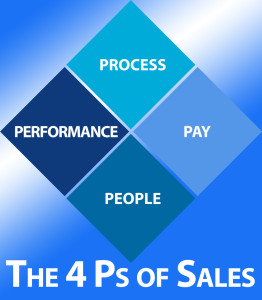

The second “P” in my “Four Ps of Sales” is “Performance.” In a sales context, performance represents the number of sales you need to make in order to meet your goals. To accurately gauge your performance, you first need to know what those sales goals are.

The second “P” in my “Four Ps of Sales” is “Performance.” In a sales context, performance represents the number of sales you need to make in order to meet your goals. To accurately gauge your performance, you first need to know what those sales goals are.

This means getting a firm grip on your expenses and your revenue needs. A surprising number of people find this part of the sales process intimidating, as it involves a little number crunching. It’s not that this math is complex — it’s pretty basic stuff, actually — but any time you have to break out a calculator, a certain percentage of people’s eyes start to glaze over.

It’s not always easy to make financial projections seem lively. You might not be on the edge of your seat as you read this post, but I’ll do my best to keep this part as painless as possible.

Let me start by saying that it’s much easier for an existing business to generate sales performance data. You already have goals, an operating history, and known expenses to use as a baseline for improvement. This doesn’t mean a startup can’t use the same methods for creating performance targets, it’s just that those numbers will be a little more speculative, and will need to be revised as the real data comes in. In any case, it’s good practice to think about performance goals, even if you aren’t yet ready to start selling.

Sales performance is also a situation where your assumptions and results will change over time. To get the most meaningful results, I like to employ a kind of reverse-engineering of a profit-and-loss (P&L) exercise. In essence, this measures: How much you sold, how much it cost to sell those things, and what is the cost to keep the business itself open. Whatever is left over is your profit or loss. Let’s take a look at these individually.

How much did you sell? This is your revenue. It’s a pretty easy number to nail down. Just add up the dollar value of everything you sold.

How much did it cost to sell those things? This is a little more complex, and it’s a little less obvious what counts. This can include things like the cost of the goods and raw materials, implementation costs and sales commissions. Some costs are also industry or business model specific, so what counts really depends on the business that you’re in. Subtract this number from the amount you sold, and what’s left over is called the “gross profit.”

How much does it cost to keep the business open? This is stuff like rent, utilities, payroll, loan payments, insurance and other fixed expenses. These are also called your “operating expenses” or “overhead.” Subtract this amount from your gross profit, and you have either a positive number (profit) or a negative one (loss).

With this basic P&L exercise out of the way, we have a starting point for looking at performance. You’ve established the fixed and variable expenses, allowing you to start folding a portion of those costs into every sale. Now we can start to break down the number of sales you need to meet those expenses.

The next step is to create a “typical sale,” a blended average of a representative set of sales over a given time period. Instead of focusing on the success rates for individual salespeople or specific products, the goal here is to combine all that stuff together to create a composite image. This isn’t meant to be your most common type of sale, it’s more of a simplified stand-in for all of your sales.

This is easy math to do. Just combine all of your sales revenue for a specific period, and then divide it by the number of sales made during that period. If you have $1,000 in sales over a month, and you made 10 sales during that time, the average sale is going to be $100.

Once you have this number, you need to figure out how much it costs the company to make that typical sale. If you’re selling widgets, this could be the cost to make the widget, ship it, and pay the processing fee on the credit card purchase. It might also include the commission of the salesperson. If the typical sale is $100, each sale might cost $30. The $70 that remains in the gross profit margin.

We also have to consider the cost of running the business. By dividing your operating expenses by your number of sales, you can see the dollar value of that overhead on every sale. Subtract this amount from the gross profit margin, and the number you are left with is the actual profit.

Hopefully, that number is positive. If it isn’t, the business isn’t profitable. It will keep losing money until something in this equation changes. This can mean making more sales, reducing the costs of making each sale, or lowering the overhead. If nothing changes, the business loses money. When you run out of money, it’s game over.

That said, it’s not uncommon for startups to have a negative number — a loss — when they’re getting the business off the ground. Startups have special expenses, like deposits, set-up fees and one-time purchases. Getting over that hump, and getting that final number back into the positive, is what separates a successful startup from a failed one.

Don’t let this scare you. If every startup had to break even from day one, there would be no new businesses. It’s just not realistic. That’s why you have things like financing and investors to help companies bridge the performance gap.

I’ll talk about getting to the other side of that gap in my next post.